Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. was created in 1987 to churn out chips for companies that lacked the money to build their own facilities. The approach was famously dismissed at the time by Advanced Micro Devices Inc. founder Jerry Sanders. "Real men have fabs," he quipped at a conference, using industry lingo for factories.

These days, ridicule has given way to envy as TSMC plants have risen to challenge Intel at the pinnacle of the $400 billion industry.

What Intel investors really worry about is that the largest internet companies will start making their own chips. This week, Amazon.com Inc., the biggest cloud-computing company, announced its first in-house server processor. The Graviton is made by TSMC, and it supports a new version of an Amazon cloud service that's more than 40 percent cheaper than a similar offering powered by Intel chips, the company said.

https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2018-11-28/intel-s-chipmaking-throne-is-challenged-by-a-taiwanese-upstart?__twitter_impression=trueTaiwan's TSMC Could Be About to Dethrone Intel

For more than 30 years, Intel Corp. has dominated chipmaking, producing the most important component in the bulk of the world's computers. That run is now under threat from a company many Americans have never heard of.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. was created in 1987 to churn out chips for companies that lacked the money to build their own facilities. The approach was famously dismissed at the time by Advanced Micro Devices Inc. founder Jerry Sanders. "Real men have fabs," he quipped at a conference, using industry lingo for factories.

These days, ridicule has given way to envy as TSMC plants have risen to challenge Intel at the pinnacle of the $400 billion industry. AMD recently chose TSMC to make its most advanced processors, having spun off its own struggling factories years before.

TSMC's threat to Intel reflects a sea change in chipmaking that's seen one company after another hire TSMC to manufacture the chips they design. Hsinchu-based TSMC has scores of customers, including tech giants Apple Inc. and Qualcomm Inc., second-tier players like AMD, and minnows such as Ampere Computing LLC. The explosion of components built this way has given TSMC the technical know-how needed to churn out the smallest, most efficient and powerful chips in the highest volumes.

Photographer: Patrick T. Fallon/Bloomberg

"It's a once-in-a-50-year situation," said Renee James, the former No. 2 at Intel who heads startup Ampere. Her company is less than two years old and yet it's going after Intel's dominant server chip business. That Ampere thinks it can compete is a testament to stumbles by Intel, and TSMC's ability to benefit from those mistakes.

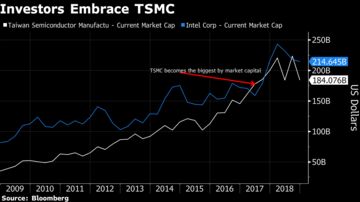

It's been a decade since Intel faced major competition and its 90 percent revenue share in computer processing will again deliver record results this year. But some on Wall Street are concerned, and rivals are emboldened, because TSMC has a real chance to replace Intel as the best chipmaker in the business. Last year, the Taiwanese company amassed a bigger market value than its U.S. rival for the first time.

What Intel investors really worry about is that the largest internet companies will start making their own chips. This week, Amazon.com Inc., the biggest cloud-computing company, announced its first in-house server processor. The Graviton is made by TSMC, and it supports a new version of an Amazon cloud service that's more than 40 percent cheaper than a similar offering powered by Intel chips, the company said.

Without TSMC's capabilities, Amazon wouldn't have the option to go it alone, according to Matt Garman, a vice president of Amazon Web Services. "More competition in this space is great," he said.

Production bragging rights in semiconductors are judged by the width of the space between lines on the tiny circuits that give chips their function. Shrinking that gap -- measured in nanometers, or billionths of a meter -- gives designers the ability to make chips that count faster, use less power, store more data or simply cost less. In the highest-end processors, where Intel makes most of its money, space is at a premium. A Xeon server processor crams billions of transistors into an area the size of a postage stamp.

Intel was the first to use 14-nanometer technology at scale in 2013, according to Goldman Sachs. It won't have 10-nanometer ready for prime time until the end of 2019 -- by far the longest wait in its history. TSMC has gone from 20-nanometer to 7-nanometer production in the same time.

Intel's holdup revolves around yield, the number of good chips that emerge from each production run. In plants that cost about $7 billion and run 24 hours a day churning out millions of chips each month, the slightest hiccup can be disastrous financially. Intel hasn't ironed out enough of these manufacturing wrinkles yet, and the company won't shift to 10-nanometer production until it's sure everything works properly.

Photographer: Suzanne Cordeiro/AFP via Getty Images

Sanders' current successor at AMD, Chief Executive Officer Lisa Su, doesn't have to worry about this because the company sold its factories and lets TSMC handle the complex production.

"That's one of the best decisions we've made," said Su. "It allows us to manage risk and focus on the things that make the product great."

With TSMC's help, Su is pursuing a goal that Sanders never attained: A credible and lasting challenge to Intel's hold on computing. AMD is now telling investors and customers that its new chip designs will surpass those from Intel. TSMC makes this competition possible, even though AMD has about a tenth of Intel's workforce and R&D budget.

TSMC didn't catch Intel all by itself, though. The company's real break came a decade ago when the smartphone began filling consumers' pockets. Intel dabbled in mobile chips, but the U.S. company never committed its best production and design to the area, preferring to prioritize its existing cash cow PC and server chip businesses.

When smartphone sales took off, phone makers used other processors from companies like Qualcomm. Or they designed their own using ARM technology, like Apple. And TSMC factories churned these components out.

The smartphone business is now almost six times as big as the PC industry by volume. That's given TSMC the advantage of high-volume manufacturing experience that previously belonged to Intel.

With billions of transistors on chips, a problem with a small number of those tiny switches can render the whole component useless. Production runs can take up to six months and involve hundreds of steps requiring maniacal attention to detail. Each time there's a mistake, the factory operator has a chance to make tweaks and try a new approach. If the change works, that information is retained to try on the next challenge. The more production runs, the better. And TSMC has the most nowadays.

"TSMC just continues to deliver latest chips on schedule without any mistakes," said Mark Li, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein. He thinks Intel's leadership in PC and server chips, plus its pricing power, are at risk because of its smartphone slip and TSMC's hard-earned consistency.

Still, this is far from the first challenge Intel has faced. The company is working on its production problems, and in the meantime will deliver new chips built with existing production technology that it says will keep the opposition at bay.

Navin Shenoy, head of Intel's server division, argues nanometer-based production measures have never been the only factor of success (although the company liked to talk about this more in the past). Intel's near-term solution is to design better chips using the old production technology.

"I'm confident that we're going to deliver what our customers care about, which is system performance," he said.

Historically, the company has squashed rivals using a research budget that dwarfed anything else in the industry. But TSMC's approach is even undermining this advantage.

While Intel still outguns TSMC in capital spending on new plants and equipment, the tables are turned when you combine the research budgets of TSMC customers like Qualcomm, Apple, Nvidia Corp. and Huawei Technologies Co.

According to Goldman Sachs, the combined budgets of TSMC's customers are not only larger than Intel but the gap is increasing. By 2020, they will spend almost $20 billion, according to its estimate, at least $4 billion more than Intel.

"They're a self-fulfilling prophesy now," said Debora Shoquist, executive vice president of operations at Nvidia. "They are the best and the best go to the best."

(Updates with Amazon chip details in seventh paragraph.)